Growing Population and Job Creation Challenge

Job Creation Gap

Job Creation Gap

The Clock is Ticking: Meeting Sub-Saharan Africa’s Urgent Job Creation Challenge Sub-Saharan Africa urgently needs to create jobs for its growing population, especially in fragile and conflict-affected states, and low-income countries.

The region’s labor markets are characterized by high levels of informality and significant barriers to job creation, resulting in too few good jobs. To tackle this, broad-based and inclusive productivity growth, including in the informal sector, is crucial. Transforming informality into a viable pathway for employment requires targeted worker-level policies and the removal of obstacles to firm growth. These efforts should be complemented by policies that support structural transformation towards higher productivity activities to expand meaningful employment opportunities.

Fragile, Low-income countries face an urgent need to create jobs… As the rest of the world grapples with population decline, Africa’s population is booming. By 2030, half of the increase in the global labor force will come from sub-Saharan Africa, requiring the creation of up to 15 million new jobs annually.1 This challenge is particularly acute in fragile, conflict-affected and low-income economies, which account for nearly 80 percent of the region’s annual job creation needs.

These countries face high fertility rates, with youth populations yet to peak. For example, Niger, with a current population of 26 million people and a youth population share not expected to peak until 2058, will need to create 650,000 new jobs annually for the next 30 years. In contrast, many middle-income countries like Botswana, Ghana, Namibia, and Mauritius have seen their youth shares of populations peak and will face less severe job creation pressures.

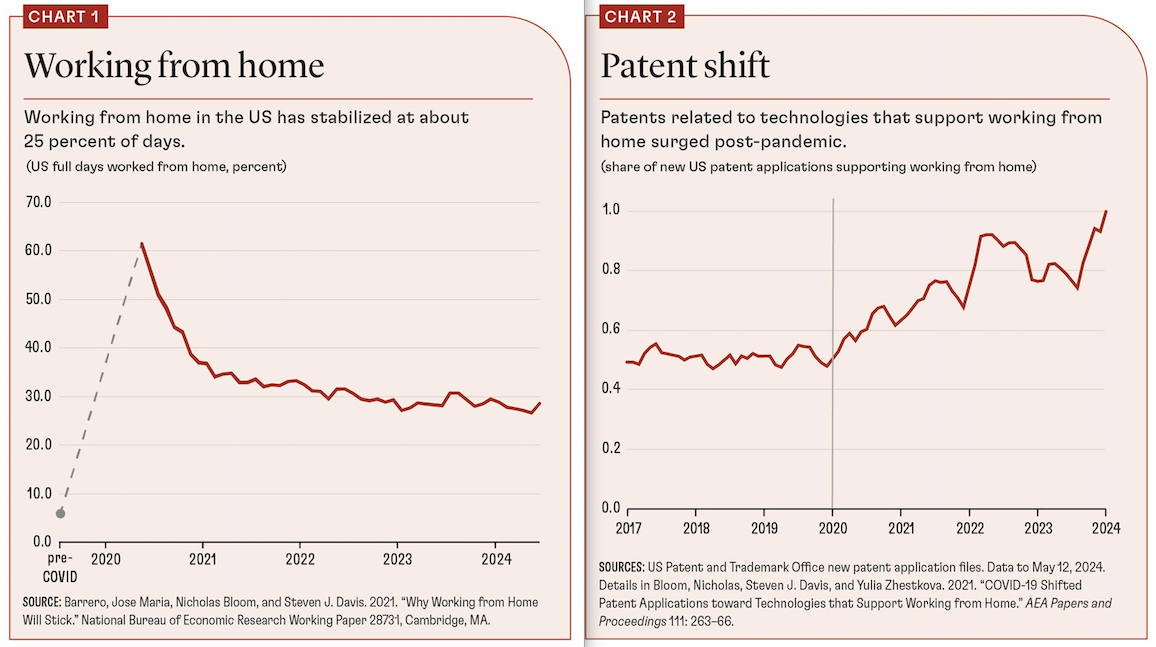

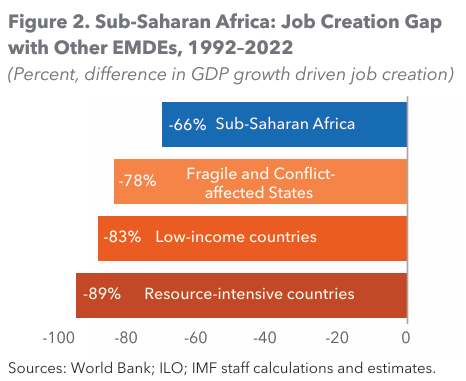

Harnessing Africa’s booming population growth potential requires generating vast numbers of productive, quality jobs that provide above-subsistence-level income, whether within structured enterprises or through self-employment. Without sufficient jobs, poverty and food insecurity will rise, increasing the likelihood of social tension, conflict, and instability. A lack of economic opportunities can also drive migration, primarily within sub-Saharan Africa but increasingly beyond the region (Kanga and others 2024). …yet labor markets fail to produce enough jobs. Sub-Saharan Africa’s growth generates relatively fewer jobs compared to other emerging markets and developing economies.

The region produces only one-third of the jobs observed elsewhere with similar GDP per capita increases. This issue is particularly acute for low-income, fragile and conflict affected states— precisely those under severe demographic pressures. Resource-intensive economies in the region fare even worse, creating only one-tenth of the typical number of jobs from economic growth due to reliance on low- employment extractive activities. As a result, economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa has been less effective at reducing poverty, achieving only about half the impact observed in other regions (World Bank 2013; Wu and others 2024). The region’s employment landscape is dominated by subsistence-level jobs, with fewer than one in four workers holding wage employment.

Over a third are classified as working poor, earning less than $1.90 per day. Underemployment is also extremely high, particularly in rural areas reliant on seasonal agriculture. To address the challenges hindering the creation of well-paying, quality jobs in sub-Saharan Africa, it is crucial to examine the underlying barriers affecting both labor demand and supply. The following sections explore three key impediments: the prevalence of informal jobs, constraints to firm growth, and limited labor demand amidst high concentrations of low-productivity sectors.

Jobs are mostly informal, especially for youth and women In sub-Saharan Africa, informality dominates the employment landscape, with around 8 in 10 jobs classified as informal (ILOSTAT). These jobs, lacking legal recognition, protection, secure contracts, benefits, and social security, are often insecure and less productive than formal sector jobs (2017 May REO). Informal production in the region accounts for 21 to 54 percent of GDP, with greater shares in low-income countries (Medina and Schneider 2018 and IMF staff calculations). However, not all informal jobs are the same. Danquah, Schotte and Sen (2021) distinguish between lower-tier informal jobs, characterized by poor pay and conditions, and upper-tier informal jobs that offer better pay and training. Across Ghana, Tanzania, and Uganda, almost 70 percent of all non-farm workers are in lower-tier informal employment (Figure 3), with an over-representation of women. Unfortunately, workers in the lower-tier informal employment struggle to move up the job ladder to better quality jobs. For example, in Uganda, fewer than 5 percent of workers are able to use lower-tier informal employment as a stepping-stone to formal employment. In contrast, workers in upper-tier informal jobs are more likely to move into formal employment, gaining higher wages and legal protections.

Young people in sub-Saharan Africa, especially young women, face particularly steep obstacles to securing higher-quality jobs, including a shortage of available formal jobs. Many end up in lower-tier informal work or unemployed, leading them on a path of instability. Over one in four young Africans are not in education, employment or training, with two-thirds of those being young women (ILO 2024). Barriers include skills mismatch, restricted access to professional networks, and a lack of critical job market information. Young women are often limited by domestic responsibilities and face discrimination. The experience paradox, where a lack of work experience hinders entry into the formal sector, is worsened by the limited availability of jobs, putting young people at a disadvantage compared to older cohorts. Almost 40 percent of young men and 50 percent of young women have been looking for a job for over a year, with longer unemployment spells increasing the likelihood of transitioning into unstable, informal work.

Given its ubiquitousness, the informal sector is a critical source of employment for sub-Saharan Africa, especially where formal opportunities are scarce. A key transformation required for the region is helping the workforce climbing up the job ladder, moving out of subsistence and lower-tier informality to higher-tier informal employment and formal jobs. Firms face many constraints to growth Sub-Saharan Africa outpaces other low- and middle-income countries in new firm creation per working-age adult (World Bank Entrepreneurship Database). Despite this promising start, firm growth remains elusive, with most businesses remaining small, low in productivity, and unregistered, often run by sole proprietors.

This results in a large number of micro firms but a shortage of medium and large firms, which are essential for job creation, as seen in other regions (Abreha and others 2022). African firms cite access to finance, electricity, and informal sector practices as their biggest growth obstacles, far surpassing those faced by global comparators (World Bank Enterprise Surveys). For example, securing an electricity connection in Nairobi takes about 92 days, more than double the average for other countries with similar incomes, while across the region, frequent power outages significantly reduce firm sales, productivity, and employment (World Bank Enterprise Surveys, Cole and others 2018, Mensah 2024). Small firms particularly struggle to access the working capital required to scale their enterprises, often resorting to informal lenders (Nwajiuba and others 2020, Runde and others 2021). After overcoming initial hurdles, businesses face challenges in expanding due to limited domestic demand and restricted access to international markets (Teal 2023). Bureaucratic regulations, corruption, inadequate infrastructure, and comparatively high labor costs compound these challenges (Gelb and others 2014, 2020; World Economic Forum, 2017). Despite these barriers, a significant portion of formal businesses originate from small informal enterprises, indicating that informality can serve as a stepping-stone (Adom 2024). For instance, over one-third of formal sector firms in Angola started unregistered, a trend seen in over 20 percent of firms in a quarter of the surveyed sub-Saharan African countries (World Bank Enterprise Surveys). Currently, the public sector fills part of the employment gap, accounting for nearly a third of wage jobs in the region (Bhorat and Oosthuizen 2020), especially in many resource-intensive countries (October 2024 REO—Note “One Region, Two Paths: Divergence in Sub-Saharan Africa”). Public positions are lucrative; in Lesotho, Namibia, Rwanda, and Togo, public sector wages are over four times higher than private sector wages (World Bank Global Jobs Indicators 2020), making it challenging for private sector firms to attract workers (Thevenot and Walker 2024). However, the public sector cannot sustain job creation alone. Thus, fostering private sector firm growth is a second major transformation required for the region.

18-11-2024